There is a popular ‘myth’ that smallpox was responsible for the devastating loss of life suffered by the indigenous peoples of America, because it was ‘carried’ there by Europeans. Variations of this story also refer to other diseases carried to the New World by the Spanish initially and later by the Portuguese and the British. These diseases include measles, influenza, bubonic plague, diphtheria, typhus, cholera, scarlet fever, chicken pox, yellow fever and whooping cough; it is commonly asserted, however, that smallpox was responsible for the greatest loss of life.

Within this myth are a number of interrelated assertions, one of which is that none of these diseases had previously existed in the New World. Another is that, because these diseases were ‘new’ to them, the indigenous people had no immunity and were therefore unable to offer resistance to ‘infection’ with the germs carried by the Europeans. The inevitable conclusion, according to the myth, is that millions of people became ‘infected’ and therefore succumbed to, and even died from, the diseases the germs are alleged to cause.

However, nothing could be further from the truth.

Although the main reason this myth is false is because it is based on the fatally flawed ‘germ theory’, its assertions can also be shown to be in direct contradiction of a number of the claims made by the medical establishment about ‘infectious’ diseases.

One of these contradictions arises because few of the diseases alleged to have been ‘carried’ to the New World are regarded as inherently fatal, but they are claimed to have caused millions of deaths. Yet, if these diseases were so deadly to the indigenous peoples, how were any of them able to survive; as there clearly were survivors.

It is claimed that the crews of the ships that arrived in the New World spread their diseases easily because they are highly contagious. It is also claimed that these sailors remained unaffected by the germs they ‘carried’ throughout the long voyages across the Atlantic Ocean. Although some people are claimed to be ‘asymptomatic carriers’, it is highly improbable, if not impossible, that every crew member of every ship that sailed to the New World would have merely carried the ‘germs’ without succumbing to the diseases.

The most common explanation offered for the failure of the crews to succumb to these diseases is that they had developed immunity to them; but this explanation is highly problematic. According to the medical establishment, a healthy, competent immune system is one that contains antibodies that will destroy pathogens. Therefore, if the European sailors were ‘immune’ to all these diseases due to the presence of the appropriate antibodies, their bodies would not contain any ‘germs’. If, on the other hand, the European sailors did carry ‘germs’ they could not have been ‘immune’.

It is not the purpose of this discussion to deny that millions of people died, but to refute the claim that they died from ‘infectious diseases’, especially smallpox, because they had no ‘immunity’ to the ‘germs’ transmitted to them by Europeans. This refutation means therefore, that they must have died from other causes.

Fortunately, historical research has uncovered evidence of the existence of a number of causal factors that would have contributed to the devastating loss of life in the New World after 1492. One source of research is the work of historian Dr David Stannard PhD, who studied contemporary writings during his investigation of the history of the discovery of the New World. This research is documented in his book entitled American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World, in which he reveals many pertinent factors, not least of which relates to the conditions in which most Spanish people lived during the period prior to the first voyages to the New World; he explains,

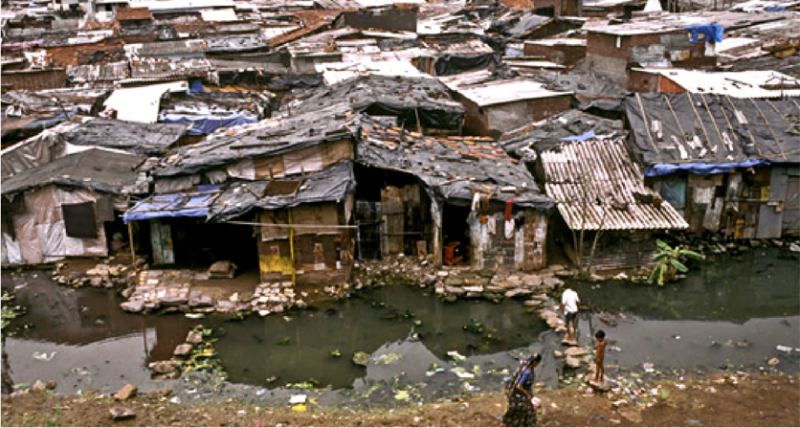

“Roadside ditches, filled with stagnant water, served as public latrines in the cities of the fifteenth century, and they would continue to do so for centuries to follow.”

These conditions are strikingly similar to those that prevailed in many European countries during the same period. The majority of the people lived without sanitation or sewers; they lived with their own waste and sewage. Those who lived in towns and cities had limited, if any, access to clean water, which meant that they drank polluted water and rarely washed themselves. The majority of the populations of these countries were also extremely poor and had little to eat. In his book, Dr Stannard quotes the words of J H Elliott, who states,

“The rich ate, and ate to excess watched by a thousand hungry eyes as they consumed their gargantuan meals. The rest of the population starved.”

Insufficient food that leads to starvation is certainly a factor that contributes to poor health, but eating to excess can also be harmful to health; which means that the rich would not have been strangers to illness either. It is not merely the quantity of food, whether too little or too much, that is the problem; of far greater significance to health is the quality of the food consumed.

The conditions in which the native populations of the New World lived were, by comparison, strikingly different; as Dr Stannard relates,

“And while European cities then, and for centuries thereafter, took their drinking water from the fetid and polluted rivers nearby, Tenochtitlan’s drinking water came from springs deep within the mainland and was piped into the city by a huge aqueduct system that amazed Cortes and his men – just as they were astonished also by the personal cleanliness and hygiene of the colourfully dressed populace, and by their extravagant (to the Spanish) use of soaps, deodorants and breath sweeteners.”

One of the most significant contributions to the substantial reduction in morbidity and mortality from disease, especially smallpox, in Europe was the implementation of sanitary reforms. It is therefore wholly inappropriate to claim that people who lived in such clean and hygienic conditions would have been more susceptible to disease. In reality, the people who lived in such clean and hygienic conditions would have been far healthier than any of the colonists, all of whom lived in countries where most people lived in squalid conditions, amidst filth and sewage and rarely, if ever, bathed.

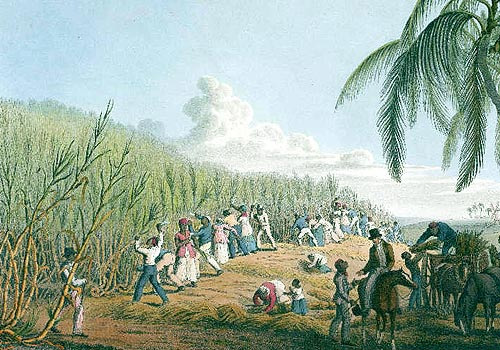

The original objective of the first voyage led by the Italian, Christopher Columbus, is said to have been to find a western route to Asia; however, the main purpose of the voyages to new lands was to seek and obtain valuable resources, such as gold and silver. When the conquistadors observed the golden jewellery worn by indigenous peoples, they assumed that the land was rich with such treasures and this resulted in atrocious behaviour, as Dr Stannard describes,

“The troops went wild, stealing, killing, raping and torturing natives, trying to force them to divulge the whereabouts of the imagined treasure-houses of gold.”

Using these methods, the Spanish ‘acquired’ the gold and jewellery they desired, but when no more could be collected directly from the people, they proceeded to utilise other methods. One of these methods was to establish mines, using the local population as the work force, to extract the precious metals from the ground. In addition to being forced to work, the indigenous peoples endured appalling conditions within the mines, as Dr Stannard explains,

“There, in addition to the dangers of falling rocks, poor ventilation and the violence of brutal overseers, as the Indian labourers chipped away at the rock faces of the mines they released and inhaled the poisonous vapours of cinnabar, arsenic, arsenic anhydride and mercury.”

To add insult to injury, the lives of the Indians were viewed by the Spanish purely in commercial terms, as Dr Stannard again relates,

“For as long as there appeared to be an unending supply of brute labor it was cheaper to work an Indian to death, and then replace him or her with another native, than it was to feed and care for either of them properly.”

Mining was not the only type of work they were forced to perform; plantations were also established, with the local population again comprising the total labour force. The appalling conditions and the violence they suffered led to their lives being substantially shortened; as Dr Stannard further relates,

“It is probable, in fact, that the life expectancy of an Indian engaged in forced labor in a mine or on a plantation during those early years of Spanish terror in Peru was not much more than three or four months…”

The number of deaths that resulted from such brutal work and treatment is unknown, but clearly substantial, as indicated by author Eduardo Galeano, who describes in his book entitled Open Veins of Latin America, that,

“The Caribbean island populations finally stopped paying tribute because they had disappeared; they were totally exterminated in the gold mines…”

It is hardly surprising that so many died in the gold mines considering the conditions they were made to endure; these included exposures to many highly toxic substances, as described above.

There was a further and even more tragic reason that many people died, but this did not involve brutal work and appalling working conditions. It is reported that some of the native people refused to be enslaved and forced to work; instead they took their fate into their own hands, the tragic consequences of which are explained by the words of Fernandez de Oviedo as quoted by Eduardo Galeano in Open Veins,

“Many of them, by way of diversion took poison rather than work, and others hanged themselves with their own hands.”

The number of people who died this way is also unknown, because these events were mostly unrecorded. Dr Stannard writes that there was a considerable level of resistance by the native people that often led directly to their deaths at the hands of the conquistadors, but the number of people who died this way is also unknown.

Dr Stannard states that ‘diseases’ were also a factor that caused the deaths of many of the indigenous people. Unfortunately, in this claim, like the overwhelming majority of people, he has clearly accepted the medical establishment claims about infectious disease. Although this reference to diseases must be disregarded, Dr Stannard’s research is otherwise based on documented evidence; for example, he refers to eyewitness accounts written by people such as Bartolomé de Las Casas about the atrocities that devastated the native population. Dr Stannard also refers to documented reports, which state that many tens of thousands of indigenous people were directly and deliberately killed; he refers to these as massacres and slaughters.

Dr Stannard records that many native people attempted to retaliate but were invariably unable to overpower the conquistadors who had superior weapons; many of them died as the result of these battles. Others chose not to fight but instead attempted to escape, the result of which was that,

“Crops were left to rot in the fields as the Indians attempted to escape the frenzy of the conquistadors’ attacks.”

Starvation would no doubt have accounted for many more deaths.

The enormous scale of the loss of life can be illustrated by statistics that relate to the indigenous population of Hispaniola, which Dr Stannard reports to have plummeted from 8 million to virtually zero between the years 1496 to 1535. He indicates that this devastation in Hispaniola was not unique; but represents a typical example of the almost total annihilation of the indigenous populations that occurred throughout the land now known as America.

The Spanish were not the only ‘conquerors’ of the New World; the Portuguese established themselves in Brazil soon after the Spanish had arrived in Hispaniola. The consequences for the indigenous population of Brazil were, however, virtually the same as those for Hispaniola, as Dr Stannard records,

“Within just twenty years…the native peoples of Brazil already were well along the road to extinction.”

The arrival of British settlers, beginning in 1607, saw no reprieve for the indigenous peoples; although the confrontations were initially of a more ‘military’ nature; Dr Stannard relates that,

“Starvation and the massacre of non-combatants was becoming the preferred British approach to dealing with the natives.”

The medical establishment has a clear vested interest in perpetuating the myth that it was the ‘germs’ that killed many millions of people who had no immunity to the diseases the germs are alleged to cause.

Unfortunately, this myth has distorted history, as it has succeeded in furthering the ‘germ theory’ fallacy, and failed to bring to light the real causes of the deaths of many millions of people; but, as the work of people like Dr David Stannard, Eduardo Galeano, and others, have shown, there is ample evidence to support other and more compelling explanations for that enormous death toll, all of which may eventually succeed in overturning the myth.

Dawn Lester

9th July 2020

STANNARD, D. – American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. 1992.

GALEANO, E. – Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. Serpent’s Tail. 2009.